The truth about what killed the legendary kung fu star Bruce Lee… and the coverup that followed.

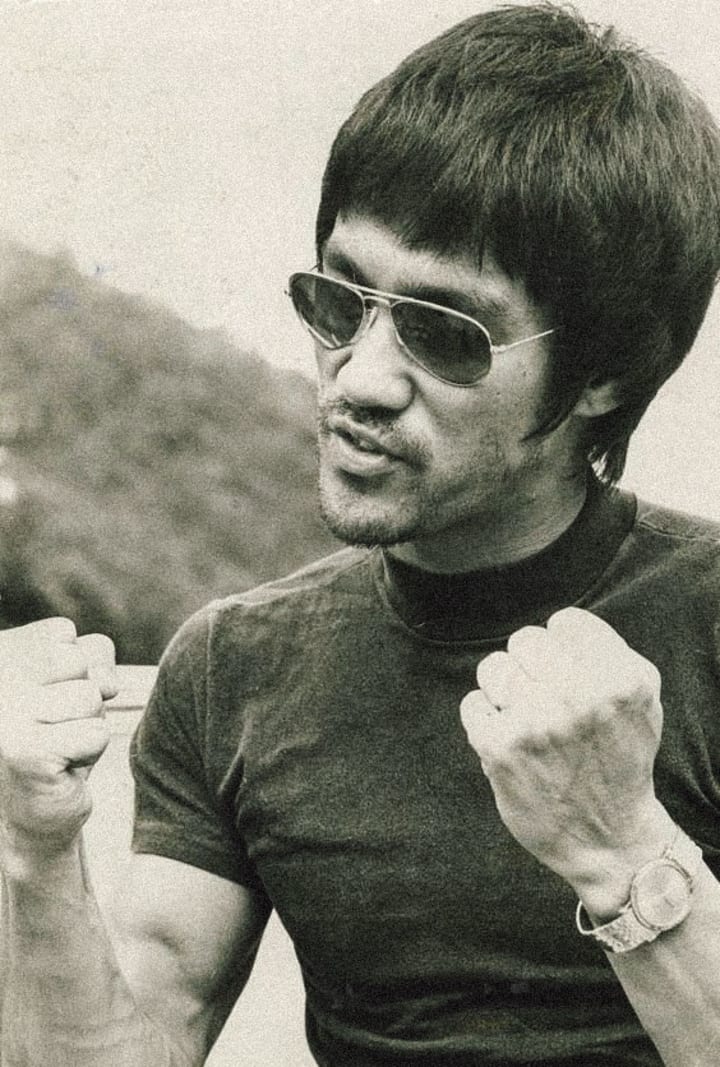

All the witnesses agree: during the last months of his life, Bruce Lee was heading for a crack-up. No matter how you sized him up, the danger signals were unmistakable. The most obvious signal was weight loss. During his best years, Lee—who stood between 5' 6" and 5' 7" and was very lightly boned—built himself up through diet and exercise to a peak of 155 pounds. Now this extra poundage began to melt away. Eventually, he went down to 120. When Danny Inosanto, Lee's principal disciple, saw his master for the last time, he was shocked by the change in his appearance. “You’re too thin!” he warned. “How are you going to get your full power?” "My full power?” hissed Lee, “How about this?” With that he gave Inosanto a shoulder shot that sent the disciple flying 12' across the room. All the same, Lee was concerned about his inexplicable weight loss. His solution was to adopt a particularly nauseating diet: congealed bull's blood mixed with raw hamburger steak.

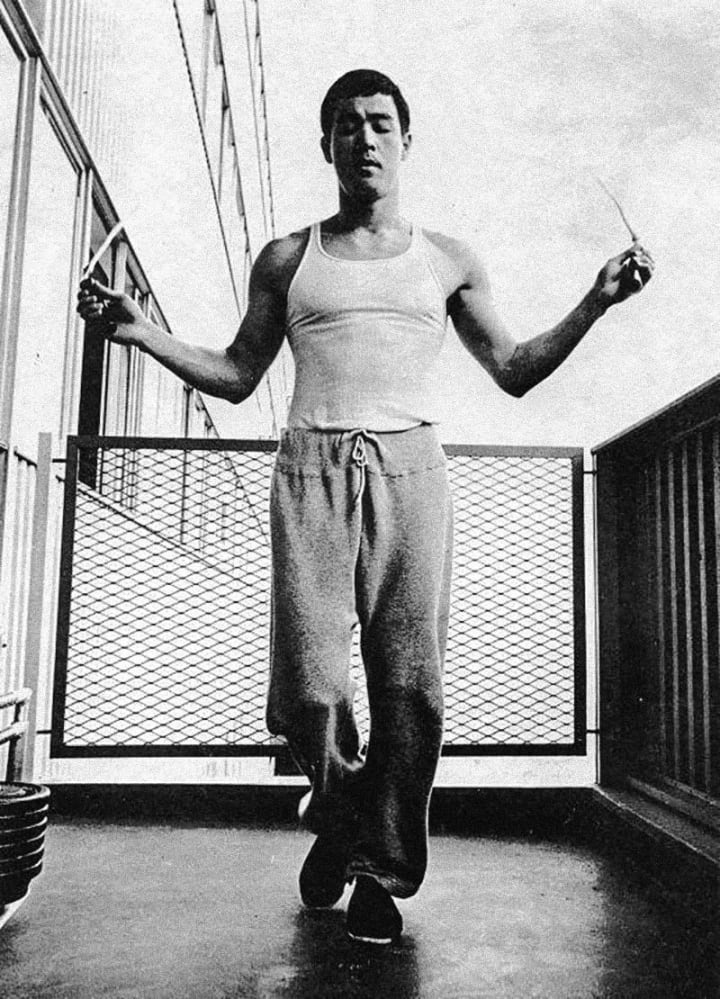

A more serious sign that Bruce Lee was in trouble was the startling fact that he had abandoned his exercise routine. A fanatic about physical conditioning and training, Lee had spent the better part of his life running, doing calisthenics, lifting weights, practicing martial-arts exercises, and sparring with his students. Believing that running was the best exercise, he did 2 to 6 miles of road work every day and pedaled 10 to 20 miles every other day on a stationary bicycle. To achieve the ultimate in muscular strength and coordination, he had filled almost every room of his house in Hong Kong with martial-arts gear and exercise machines, most of the latter designed to his own specifications. Now, though, he spent most of his time locked up in his second-floor study, talking frantically on his telephones, sketching scenarios, and holding business conferences.

Money Problems

Money occupied the center of Lee's mind in his last days. After a lifetime of barely breaking even, he was determined now that he was famous enough to make—and keep—a fortune. His ideas of finance were pretty crude. Basically, he was concerned with hiding his wealth. He put his $250,000 house in the name of his “butler,” Wu Ngan, so that in the event of a divorce his wife couldn't claim a share in the property. A more important consideration was how to hide his money from the IRS; for Lee was intent upon returning to Hollywood now that he was a superstar, but he dreaded the thought that the American government would take an enormous bite out of his earnings. When he sought the advice of Werner Wolfen, one of the smartest tax men in Los Angeles, he was told firmly by this expert (who saw Lee as a “street person’’) that he would not participate in any illegal schemes. Lee left the lawyer's office in high dudgeon. Just before he died, however, Lee sent the tax expert a handwritten note agreeing to follow his advice. This pattern of defying reason and then reversing himself was highly characteristic of Lee. It was the yin and yang of his reckless and impulsive temperament.

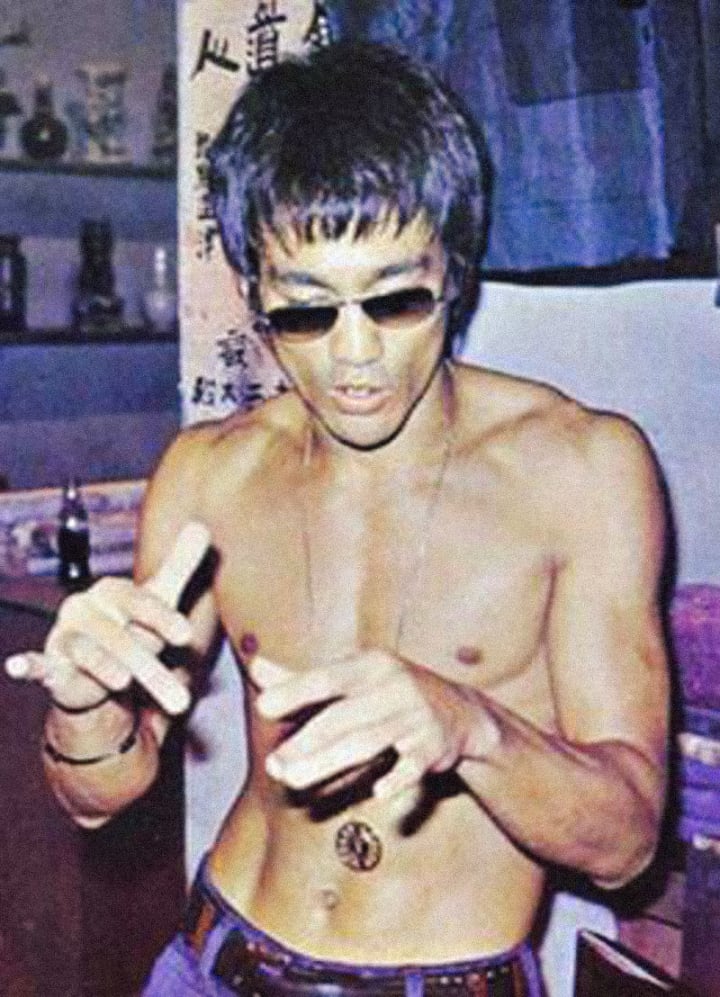

Another reason that Bruce Lee spent so much time holed up inside his walled villa (not a mansion, by any means, but a narrow, two-story Japanese-style house with its back to a railroad track) was that he was suffering from paranoia. During his final months, Lee fancied himself, like a character in one of his films, surrounded on every side by enemies. Just as striking as the similarity between life and art, however, was the difference. In his films, Bruce Lee walks fearlessly into death traps, cloaked in the invulnerability provided by his magic arts. In real life, he craved weapons, especially weapons he could wear on his person without being detected.

So he caused to be smuggled into Hong Kong, which has very strict laws against any sort of weapon, a whole arsenal of concealed weapons. Among his deadly tools were a comb that spat out a blade like an ice pick, a tear-gas pen, a sword cane with a 12" blade, a walking stick with a .410 shotgun shell at one end and a tear-gas canister at the other, a pearl-handled .22 caliber magnum-load double-barreled Derringer (smuggled inside a 10-gallon can of Jack LaLanne protein powder), and a slew of serikens, the six-sided throwing stars that can be hurled with far greater accuracy than a knife or else held between the knuckles like a razor for slashing. Lee was not content simply to carry these weapons for self-defense. On more than one occasion, he whipped them out and brandished them with terrifying effect. Typical is the story told by Wong Nguk Chung, personnel manager of Golden Harvest Films and the editor-writer of a Bruce Lee fan magazines.

After the release of Return of the Dragon, the only completed film that Lee wrote, directed, and stunt-coordinated, Mr. Wong wrote a little notice in his fan magazine saying that Bruce Lee had “not matured yet as a director.” That was an understatement, to put it mildly. This film is far and away the worst of the Bruce Lee pictures, and the fault is entirely that of its author, director, and stunt coordinator. What Wong didn't understand when he voiced his timid little criticism was that Bruce Lee—who had always been so open, friendly, and down-to-earth in his relations with the editor of the fan magazine—was now a changed man.

No sooner did Lee read the notice than he summoned Wong to the office of the boss of the film company, Raymond Chow. The moment Wong walked through the door, he got an order from Lee to sit down. Then the famous star fixed the frail little editor with his most deadly basilisk stare, and clenching his teeth in precisely the manner he used in all his films to warn the villain that his time was near, Lee proceeded to teach the writer his lesson.

Unexpected Weapons

“When you take a pen,” he enunciated with pedantic but terrifying precision, "it's exactly as if you took a knife or a gun. One slip and you’ve inflicted a deadly wound.” Then, just to make the point a little clearer, Lee grabbed his belt buckle and extracted from it one of those concealed knives you see advertised in mercenary magazines like Soldier of Fortune. Laying the tip of the blade precisely on the carotid artery in the editor's neck, Lee drove home his point. “My knife is just like your pen. If you criticize, you hurt!”

Wong, frozen with fear, gasped out the excuse that he had meant no harm, that his criticism was intended to act as an incentive for Lee to improve. Raymond Chow, another frail, bespectacled, professorial-looking man, chimed in with his assurances that Wong had meant well. Finally, the enraged Bruce Lee could no longer contain his rage. Turning to the office door, he gave it one of his famous kicks and sent it flying down the hall. Only then did he begin to simmer down and come to his senses. Characteristically, he wound up shaking hands and apologizing for his choleric behavior.

Editor Wong was by no means the principal offender in the local press. More frequent targets of Lee's rage were the newspapermen and especially the photographers. Though the local press worshiped Bruce Lee, it was naturally obsessed with the sex life of the man “who restored masculinity to the Chinese screen,” to quote Golden Harvest's first Bruce Lee publicity release. Lee, for his part, was enjoying sexual abundance for the first time in his life.

Brought up in an uptight environment that hadn't allowed him sexual fulfillment as a youth, involved from the age of twenty-four in a tight marriage, an obscure little Chinaman in a Hollywood that is always infatuated with the current style of occidental beauty, Bruce Lee was just now, at the age of thirty-two, having his first taste of being irresistible to women—an experience that would turn most men's heads. Unfortunately, he was not discreet in managing his liaisons. Nor is Hong Kong— congested, gossip-ridden, a Chinese village of 5 million souls—the kind of place where concealment is easy. The upshot was that every time Lee indulged himself in a passing affair with one of his co-stars or a model or a courtesan, a story accompanied by a picture of the pair would turn up in the press.

Instead of resigning himself to this provocation, Lee would invariably fly into a rage and go roaring down to the office of the paper with murder in his heart. Charging into the copy room, he would demand to know who had written the story or taken the photograph. If he found his prey, he would slap the man around or choke him by the throat and then smash his camera. When the poor wretch was scared out of his wits, Lee would make a final speech, warning in tones that could not be forgotten that the next time this happened, he would come back and massacre the entire staff. In a town with two or three papers, these tactics of intimidation might have worked. In Hong Kong, which at that time had 121 dailies, there was always a fresh team of newsmen ready to risk their necks to get a hot scoop on the “Dragon.”

Threatening His Professional Relationships

The most serious aspect of Bruce Lee's bizarre behavior was the threat it posed to his most vital relationships, especially his professional relationships. Everybody who worked with the explosive star recognized that dealing with Lee was like handling dynamite. Every effort was made to avoid tension or quarrels. Lee's wishes were deferred to in everything; Lee was allowed to call all the shots.

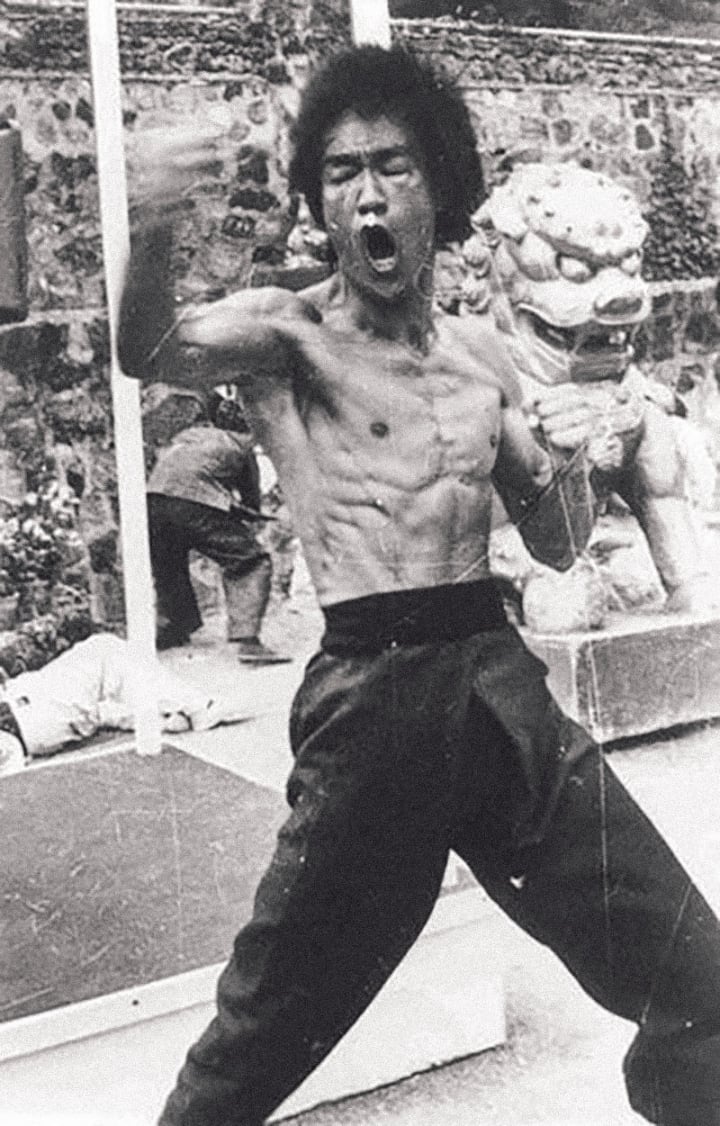

Even so, there was no way to avoid accidents in the tricky business of making movies, especially movies that focused on violent physical combat. One of the most revealing episodes from Lee's final phase is the story of his deadly confrontation with Bob Wall during the making of Enter the Dragon.

In one scene, Wall, playing a villain, attacks Lee with two jagged-edged broken bottles. Lee knocks the bottles out of Wall's hands with a spinning kick, then he raises his hand to counter the next attack. The first time the scene was tried, Lee missed his kick, and when he spun around with his raised fist, he scored his hand against the jagged glass. The injury was not serious. At most, it would sideline Lee for two weeks. When Wall exclaimed, “Gee, I'm sorry, Bruce!" Lee snapped a curt "No problem" and left for Dr. Langford, his personal physician.

The truth was, however, that this accidental injury posed a grave problem because it caused Bruce Lee to lose face in front of the crew and the extras. Bruce Lee, after all, was regarded by the Chinese as a superman, a fighter who dealt out deadly punishment but who rarely took a blow, much less one that drew blood and put him out of action. Soon Bob Wall began to hear stories that Bruce Lee was going to murder the man who had maimed him. Wall, who had known Lee for years and recognized his sensitivity, put his head together with Fred Weintraub, the picture's producer, and came up with a solution.

One afternoon, Wall drove out to Bruce Lee's house and confronted him with the rumors that were going about. Lee denied everything, putting all the blame on the “Chinese." Wall persisted, explaining that he realized how important it was for Lee to maintain his image. Then he outlined his plan for getting the star off the hook. Lee fell in with the suggestion at once.

The first day that shooting resumed, Bruce Lee stood up in front of the assembled crew and made a short speech in Chinese. He explained that he had intended to kill Bob Wall as a matter of honor, but because Wall was an old friend and was needed to complete the picture, Lee had decided to assuage his pride by administering a terrible beating to the white devil. Wall, at this point, opened his shirt to show that he was not wearing any protective padding. Then, with the cameras rolling, the men squared off to fight.

Wall had told Lee that no matter how hard he kicked, Wall could take the blow. Now, Lee went to work with a vengeance. His first kick landed with such force that it hurled Wall into an extra standing behind him, breaking the man's arm. Eight times, Bruce Lee kicked Bob Wall—who never failed to utter loud groans and gasps—until Lee's footprints were all over Wall's chest and abdomen. Finally, the scene was wrapped.

Regained Respect

That night Lee took Wall to supper at Hugo's, Hong Kong's finest French restaurant. As they sat at the table, Lee exclaimed: “Bob, that was the greatest thing anybody ever did for me. Did I hurt you?” Wall replied that he had been hurt worse in other fights.

Though all the American karate men who worked with Bruce Lee respected him for his great abilities and remembered him fondly for the way he had been in the good old days, they grew steadily more disenchanted with his behavior in Hong Kong. Particularly those who were seeking to make a career in films resented the way they were set up in the Bruce Lee films to look like clumsy oafs who could be knocked around at will by a guy who was much smaller than they. They recognized that when the films were exhibited, the fans would not view them as dramas in which the American karate men were playing assigned parts. The public would assume that the Americans were in fact inferior fighters, big, klutzy dudes who just couldn't hold their own against the Dragon.

This struck a sore spot among the Americans because they knew that though Bruce Lee had worked out with them many times, he had never once engaged in actual competition. His excuse was that tournament fighting was unreal, like “swimming on dry land.” But when Joe Lewis (and subsequently, Bill Wallace) introduced full-contact karate, this excuse would no longer hold water. (Light-contact karate was introduced in 1963: you were not supposed to strike the face, and blows to the body were supposed to be half-pulled. Full-contact karate was introduced by Joe Lewis at Long Beach on January 17, 1970.) The feeling among the American karate men was that Bruce Lee simply didn't want to take the chances every competition fighter took of being hurt or defeated. His image, in other words, was more important to him than the actual test of combat.

The upshot of this feeling was a gradual estrangement between Bruce Lee and his old friends in the karate world. Some of the men who appeared in films with him swore that they would never repeat the experience. Others developed a rather wry and ironic attitude toward Lee, making fun of his histrionics on the screen, his poses, grimaces, and noises, none of which had any real connection with the martial arts. They especially ridiculed the notion that Lee could defeat champions who were much taller and heavier than he, or that he could take on a fighter like Muhammed Ali, each man using his own style, and walk off the winner, an idea cherished by many Bruce Lee fans. In short, the karate men protested against the illusion that was the greatest product of Bruce Lee's art, the universal conviction that he was the deadliest man on the planet.

Bruce Lee and Hashish

In the final period of his life, Bruce Lee began to rely on hashish to lift from his oppressed mind all the terrible burdens that were driving him mad. He had a young gofer who was encharged with the dangerous assignment of procuring the drug, which was smuggled in from Nepal. Like many other countries, Hong Kong has highly punitive laws against illegal drugs. Possession of even five grams of “cannabis resin" is punishable by a fine of $5 million HK and life imprisonment. Bruce Lee, an immoderate man by nature, was not the kind to limit himself to just a couple puffs on a hash pipe. In fact, he never smoked hash, because, being a nonsmoker, he had an aversion to inhaling. It was his custom to eat the drug in the form of confections. Bob Wall recalls a visit to Bruce Lee's house about six months before Lee's death during which Lee both explained and demonstrated his commitment to the drug he called "the most wonderful stuff in the world.”

Wall was sitting in Lee's second-story study when Lee offered a plate of cookies to Wall, urging, "Try some of this!'"

"What is it?" asked Wall.

“Hashish in brownies,” smiled Lee.

"I thought you were anti drugs," replied Wall, genuinely surprised that a man who wouldn't take a glass of wine would be consuming a dangerous drug. At that point, Lee whipped out a copy of the September 1972 edition of Playboy, which contained a clutch of articles entitled "The Drug Explosion.” Actually, there was nothing in any of the pieces that would make a man want to turn on, but the chart prepared by the editorial staff characterized cannabis as providing "relaxation, breakdown of inhibitions... euphoria, increased appetite"—all things that were appealing to the anxious, irritable, and underweight Bruce Lee. Most important was the fact that no distinction was drawn between marijuana and hashish: both were both lumped together indifferently beside the rubric "cannabis.”

This was a serious omission. Although grass and hash are prepared from the hemp plant, they are for all practical purposes no more the same than are wine and whiskey. Especially when eaten by high-strung types like Bruce Lee, hashish is apt to prove a nightmare drug. If it doesn't drive you crazy, it may poison you. Those little "temple balls," "fingers," and other goodies from Nepal may be contaminated by having been manufactured in one of the most primitive and unhygienic environments on earth. If you don't burn the stuff, you are asking for trouble.

Naturally, Bruce Lee, who was not basically a drug adept, knew nothing of these dangers. Yet being a classic know-it-all, he claimed to be an expert on the drug. As the astonished Bob Wall looked at the two page chart spread before his eyes and listened to Lee's machine-gun rap, he learned that hashish was vastly superior to marijuana, because instead of damaging your lungs by smoking it, you could eat it like ordinary food. The most important thing, Lee stressed, was the drug's marvelous capacity for producing relaxation. "At last I've found something to relax me!" crowed Bruce as he put one of the brownies into his mouth.

In the next 10 minutes, Bruce Lee ate three or four hash brownies. Wall recalls that the brownies had been prepared according to the celebrated recipe of Alice B. Toklas. If that is the case, Bruce Lee was consuming an enormous amount of hashish. Perhaps he had found that it took a great deal to slow him down. If this was his problem he certainly found the solution. For, as Wall recalls, in just an hour Lee was totally transformed by the drug.

Slowed Down

Prior to eating the hash, Lee had been talking a mile a minute and demonstrating a new nunchaku routine that made the sticks fly around his head like hummingbirds' wings. Then he took off his shirt and threw it on the floor, collapsing into a comfortable chair. Gradually his rate of speech slowed and slowed until finally, astonishingly, Bruce Lee fell totally silent. In all the years he had known Lee, Wall—who is no slouch at talking himself—had never seen his friend shut up. (Lee was such a compulsive talker that in Hong Kong he damaged his car almost every week because he insisted on looking directly at the person to whom he was talking as he drove.) NOW, for the first time ever, Lee was mute—and Wall was doing all the talking. Wall at first accepted Lee's judgment that eating hashish once a week was an ideal way to give himself the relaxation he could never otherwise obtain. But then Wall began to notice that Lee was suffering from memory loss, repeating himself constantly as if he had no recollection of what he had said the day or the hour just past. This symptom coupled with the weight loss and the striking pallor of his old friend were all, Wall assumed, products of work and stress. (He doesn't think this today, however.)

Nor is it likely that by the end of his life Bruce Lee was confining himself to one hash binge a week. According to his own statement, he was taking the drug to cheer himself up at the studio and to make love. It's very difficult to resist any drug that works. (It's unfortunate that Bruce Lee was so averse to smoking, because a year on Thai weed would have been good therapy for him. It would have done all the things promised by Playboy plus provided this compulsively funny man with hysterical laughs, as well as giving depth to his philosophic moods and exaltation to his budding mythological fantasies.)

When Lee finally collapsed and nearly died after eating some hashish at the studio, he was advised by his doctors to stop using the drug. Lee, always rebellious and stubborn, decided to take his case to a higher court. Within one week of his collapse, Lee was living in a bungalow behind the Beverly Hills Hotel and undergoing neurological tests designed to determine whether he was suffering from a brain lesion or some other complaint that had not been discovered in Hong Kong. The neurologist was working under a great handicap, however, because all the symptoms had vanished, and the only description of the attack was that provided by the patient and his wife, Linda, both of whom made the mistake of thinking that Lee had suffered a convulsion. In fact, Lee had not had a convulsion. He had exhibited a lot of muscle twitching, a condition to which he was prone, especially when under stress. Otherwise, his symptoms were those of a toxic brain condition produced by drugs.

Inevitably, the neurologist found nothing organically wrong with Bruce Lee; in fact, he told his patient that he had the "body of an eighteen-year-old." Lee, very frightened by what had happened, sought other opinions and was told by one doctor that it was ridiculous to blame his seizure on hashish. In fact, the doctor confided, he took the stuff himself—and it had never caused him the slightest distress. With that reassuring opinion ringing in his ears, Lee boarded a plane that took him back to Hong Kong—and the lifestyle that was killing him.

The End of Lee's Life

The end came on July 20, 1973. According to the story that appeared in the official inquest and was later parroted in Linda Lee's biography of her husband, Bruce Lee went on the last afternoon of his life to the apartment of a Taiwanese sex star, Betty Ting-pei, to have a meeting with her and Raymond Chow about Game of Death, in which Betty was to play a part. During the course of the meeting, Lee developed a severe headache, which caused him to retire to Betty's bed. There he was left by Raymond Chow, who arranged to meet with Lee later in the evening for supper at the Miramar Hotel with another actor being considered for a part in the film, George Lazenby.

When Betty Ting-pei found that she could not rouse Bruce Lee from the sleep into which he had fallen, she called Chow or he called her. In any case, the boss of the studio returned to the actress's apartment to find Lee in a coma. When all efforts to rouse him failed, an ambulance was called and the actor was received that night at Queen Elizabeth Hospital, dead on arrival.

The real story of what happened that afternoon is supplied by Bob Wall, who knew all the principals and spoke with them within a few hours of Lee's death. As Wall knew, Bruce Lee had been involved in a close relationship with Betty Ting-pei for months. The actress was one of the most sought-after sex objects in Hong Kong. Bruce Lee was very pleased with her and had promised to advance her career by getting her a part in his next film. On the fatal day, the pair had an afternoon date. Betty Ting-pei lived in a posh high rise just a few minutes' drive from Bruce Lee's house in suburban Kowloon Tong. The actress's flat was what the old newspapers used to call a "love nest," an apartment decorated like a lady's boudoir.

According to Wall, Bruce Lee arrived at three in the afternoon, and after spending some time with Betty, he ate a light meal. Judging from the autopsy, Lee had a hash brownie for dessert. Then, he began to complain of a nagging, numbing headache. (A feeling of constriction in the head is one of the commonest effects of eating hashish.) Betty Ting-pei did not have any Aspirin, but she had a pill of similar effect that had been prescribed by her doctor for menstrual distress. This drug, Equagesic, is compounded partly of Aspirin and partly of the tranquilizer Miltown. According to Betty Ting-pei's account, Bruce Lee took just one tablet.

Lee was supposed to meet that night with Raymond Chow, but as the headache worsened, he called to ask that Chow come to Betty Ting-pei's flat. When Chow arrived, around 9:30, the meeting commenced; but it had to be broken off when Lee's headache grew so severe that he exclaimed, "I've got to lie down.” Chow chatted for another 20 minutes with the actress; then they both went into the bedroom to check on Lee.

They discovered that he could not be roused. Chow, with the memory of the recent crisis fresh in his mind, sought medical aid immediately. He dialed several doctors until he reached Betty Ting-pei's doctor, Chu Pho-hwye, who agreed to come up to the apartment at once. (That Raymond Chow did not summon Bruce Lee's regular doctor, Don Langford, who lived in the immediate vicinity and who had saved Bruce Lee's life during a previous seizure of the same sort, is probably explained by the fear of scandal.) Betty Ting-pei's doctor spent 10 minutes trying to revive Lee; then he gave up and summoned an ambulance.

At 11:24, Ambulance 24 of the Hong Kong Fire Services delivered Lee to the emergency clinic of Queen Elizabeth Hospital. The chief of the three-man ambulance crew, an experienced man, testified subsequently that he had examined Lee when he arrived at the flat. He had found no signs of life. Hence, instead of rushing Lee to the nearest hospital, he had hauled the body clear across town to the government hospital. All the same, when the hospital staff recognized who had been brought to their trauma room, they were galvanized into action. For a full half hour, they sought by every means imaginable to resuscitate the dead man. Finally, there was nothing to do but break the news to Lee's wife, who had been led to believe that there was some hope of her husband's survival, and to prepare for the enormous stink that was sure to rise the next day.

The story of the cover-up that was conducted after Bruce Lee's death has never been told. It was neither so sinister as many have believed nor so innocent as might have been hoped. The first false and misleading statement about the death was an announcement that the great star had died walking in his garden accompanied by his wife. (The reason for the lie was probably the fact that Enter the Dragon was just at the point of release and adverse publicity might have jeopardized a property worth potentially hundreds of millions of dollars.) This fib was shot to hell two days later when the ambulance driver sold his story to the press, which reported to a stunned Hong Kong on the morning of Bruce Lee's funeral that he had died in the apartment of actress Betty Ting-pei.

Betty Ting-pei, for her part, sought to wriggle out of this painful (and dangerous) situation by insisting that she had been out all afternoon shopping with her mother. This story was quickly contradicted by a neighbor, who also reported that Bruce Lee had been visiting the actress' apartment for three months, staying sometimes as long as eight hours, with his red Mercedes parked conspicuously in front of the building.

At this point, the government, which had been working vigorously behind the scenes to determine what had really happened, announced the results of a very carefully conducted autopsy, which had been performed several days after the death. The report revealed that the primary cause of death was brain swelling. Lee's brain had “swollen like a sponge,” increasing in weight from 1,400 to 1,575 grams. The report noted that cannabis resin had been found in small quantities in the stomach and small intestine, as well as the residue of the tablet of Equagesic. No evidence was discovered of disease or traumatic injury. Bruce Lee had not died a natural death.

Flames of Speculation

The release of the autopsy findings threw fresh fuel on the flames of speculation. Soon the press had printed all those fantasies about Bruce Lee's death that are still believed by millions of people the world around. There is a fantasy, in fact, for every temperament, every disposition. Those who believe in the “mysterious East" will tell you that Bruce Lee was killed by a "vibrating palm," a special blow that the victim may not notice and that does not produce its effect for days, weeks, months, or years. (Interestingly, Bruce Lee himself claimed to be able to deliver this blow.) Those disposed to attribute all mysterious deaths to the machinations of the mob argue that Bruce Lee was killed by the Triads, whose power he had supposedly defied. (This is the theme of the posthumous film Game of Death.) People in the movie business point the finger of accusation at Run Run Shaw, head of the rival studio in Hong Kong, which was actually negotiating to get Lee away from Raymond Chow when the actor died. There are even those who blame Bruce Lee's death on Chow, arguing that Lee repeatedly humiliated his boss, so much so that when Lee died, Chow's wife remarked that the death occurred just in time to save the last scrap of her husband's pride. (Lee would sneer at Chow publicly, saying: "You're nothing—I made you!") Yet other theories attribute Bruce Lee's death to the use of aphrodisiacs, evil influences on his house ("bad fung shui"), or even the mistake of using the word death in the title of his last picture. What no one wants to concede is the very great possibility that Lee may have died of an overdose of his own head.

Weeks after Bruce Lee's death, a government inquest was convened to investigate the matter. The government was by no means a disinterested party in the investigation. Several important issues hinged on the finding. For one thing, Bruce Lee was a youth hero. Every move Lee made was mimicked by thousands of youngsters. If the actor's use of hashish were blown up into a major issue, Hong Kong might soon find itself afflicted with a hashish epidemic.

Second, there was the matter of the insurance. In January 1973, Bruce Lee had taken out a policy for $500,000. If American International Assurance could prove that he had lied when he stated on the application that he had never used illegal drugs or if it could prove that he had died as a result of using illegal drugs, the widow and her children would be deprived of their insurance benefits. Finally, it was desirable in the interests of civic pride to put this shocking death in the best light possible, lest people come to believe that Hong Kong was a wicked place where dreadful things happen to even its greatest citizens. At the same time that the government was laboring to put an end to this ugly scandal, it was equally concerned to proceed with the utmost propriety and not expose itself to charges of tampering with the evidence or suppressing the facts. Fortunately, the facts were highly ambiguous. They could be interpreted in a number of ways. If the coroner's inquest chose the most innocent interpretation, the case could be concluded with no damaging consequences. So the strategy was adopted of bringing in from London a forensic pathologist of great experience who would be sympathetic to the government's concerns and whose testimony, having such weight, could exert a decisive influence on the final verdict.

To assure that this expert would not be surprised or unprepared for anything that might come to light during the inquest, a private hearing would be convened, before the public hearing, at which all the medical authorities, especially those likely to insist that the death was drug-related, would be invited to give their testimony in advance. When Bruce Lee's personal physician, Dr. Don Langford, objected that this would taint his evidence, he was told that as the inquest was not an adversary proceeding but a disinterested search for truth, there could be no harm in this little preview—though, of course, when it came time for the public hearing, each witness would testify in a manner that made it appear that he had no knowledge of what the other witnesses were deponing. The presiding figure at this rehearsal for the inquest, conducted at Queen Elizabeth Hospital about a week before the public hearing, was the respected expert recommended by Scotland Yard, R. D. Teare, Professor of Forensic Pathology at the University of London.

The Evidence and Hearing

The coroner, C. K. Egbert Tung, who conducted the inquest, and who was responsible with the three-man jury for arriving at the final verdict, was a lawyer, not a medical man with extensive scientific qualifications. To conduct such an investigation or even to comprehend the technical testimony, which had to be literally spelled out and sometimes translated into Chinese as the coroner took longhand notes, was an extremely formidable enterprise. Even if the coroner had been a highly trained forensic pathologist, however, he would have had his work cut out for him, because the Bruce Lee case entailed some very controversial issues, as well as matters into which there has never been any research.

No one, for example, wanted to say that Bruce Lee had simply died of hashish poisoning, because fatal cases of this sort are extremely rare and none that has been recorded is of absolute certainty. What Lee's physicians, Dr. Langford, and the brain specialist, Dr. Peter Wu, wanted to suggest was the possibility that Lee had developed an allergy or was hypersensitive to hashish, either alone or in combination with other drugs, such as the aspirin in the Equagesic. (Aspirin in combination with certain chemicals produces a powerful effect on the brain known colloquially as a “Mickey Finn.") Professor Teare, on the other hand, was utterly opposed to allowing any reference to hashish to appear in the finding, arguing that there were no precedents that would justify such a verdict.

The professor was clearly in error. In 1970, for example, a young athlete died at Antwerp in a room where he had been smoking hashish. The highly respected pathologist, Dr. Aubin Heyndrickx, who conducted the autopsy, made an exhaustive effort to determine whether or not hashish had been the cause of death. Eventually, through a great multiplication of the usual number of tests, he was able to rule out every other imaginable cause, leaving hashish as the presumptive cause. A year later, a French soldier tried to commit suicide by smoking a large quantity of hashish mixed with tobacco. He went into a coma for four days, but his life was saved. When he recovered, he claimed that other people had killed themselves in the same manner. Chances are that he would have died as well if there had been no medical intervention.

The strongest evidence collected for death by hashish poisoning was provided by Dr. Francis Mas, a psycho-pharmacologist on the faculty of the Albert Einstein Medical College in New York. Dr. Mas served his internship at Casablanca in 1966. He was attached to the emergency room and intensive-care unit of Averroes Hospital. It was not uncommon on a Saturday night for a patient to be brought in suffering from overindulgence in hashish. Generally, these people recovered after a night's sleep.

Once in awhile, however, such a case would exhibit precisely the symptoms observed in Bruce Lee, including coma, brain edema, and respiratory collapse. Before the doctors could reverse the process, the patient would die. Dr. Mas observed one such case personally and was told about another. The only cause for these fatal seizures that the medical staff could discover was that the victims had consumed hashish that was either very fresh or had been prepared in a manner that increased its potency.

Nepalese Hash

That Bruce Lee was consuming hashish of exceptionally high potency is quite probable in view of the drug's provenance. Nepalese hash is the most powerful in the world because it is produced by a unique process. Instead of sieving out the tops of the plants, as is done in Morocco, Lebanon, and Afghanistan—a technique that allows the product to become adulterated with inactive vegetable matter—the Nepalese wait till the sun makes the leaves of their towering plants sweat pure resin. Then they rub off this resin with their bare hands and compress it in screw presses. The resulting product is a pure concentrate of the 400 ingredients that comprise hashish. If the customer can command the best, the so-called Royal Hashish, he will obtain a drug that is often productive of violent effects, including numerous neurological symptoms. Laurence Cherniak, the only foreigner ever to study and photograph the production of Royal Hashish at close-hand, describes the effects of this preparation in The Great Books of Hashish, Volume I, as “so potent it was almost lethal.”

When the government's principal expert witness, Professor Teare, stopped debunking the notion that Bruce Lee might have perished from hashish toxicity, he was left with the task of explaining how in fact Bruce Lee did die. Strange to say, he employed precisely the same concept as that invoked by the rival doctors: the idea of hypersensitivity. Instead of inferring that Bruce Lee was hypersensitive to one or more of the 400 ingredients of hashish, Professor Teare argued that Lee had overreacted to the three ingredients of Equagesic.

At this point, the professor's bias should have been apparent to any medically qualified and fair-minded coroner, for if the medical literature contains few cases of hashish poisoning, it contains none of fatal hypersensitivity to one tablet of Equagesic. Not one of the numerous diagnosticians, neurologists, forensic pathologists, or psychopharmacologists whom interviewed concerning this case had the slightest hesitation in rejecting Professor Teare's hypothesis as untenable and even ridiculous. The Hong Kong coroner, however, for reasons best known to himself, adopted this explanation as the final finding of the court, ascribing Bruce Lee's death to "hypersensitivity to the ingredients of Equagesic.” The inquest found, therefore, that Bruce Lee, one of the best conditioned men on earth, had died of an Aspirin.

By 10 years after his death, Bruce Lee had regained his image of an immortal. He has joined the company of those rare pop heroes who not only impress their image indelibly on the consciousness of the entire world but who become forces, powers, presences, influencing the lives, and fantasies of untold millions. It needs no saying that to produce such an immense impact, a man not only must have ability but also must possess an unmatched instinct for striking just that nerve in the mass consciousness that is waiting to vibrate. In the case of Bruce Lee, this nerve contains many strands, whose distinctness is best seen by comparing the effect he has in the East with that in the West.

Bruce Lee's Legacy

The Eastern Bruce Lee—to phrase it bluntly—put balls on 400 million Chinamen. He gave his countrymen—at their moment of entrance into the great world tournament whose rules have been established by the Western powers—a hero who embodied the Western gift for aggressiveness to such an extraordinary degree that he could beat the Westerners— and their Japanese copycats—at their own bloody game. To the Westerner, on the other hand, Bruce Lee offers a fantasy escape from the feelings of terror and helplessness engendered by living in our nightmarish, violence-stalked, urban jungles.

Both Eastern and Western men suffer from the feeling of being unmanned. Both clamor for restitution of their lost sense of virility. It was Bruce Lee's function to reaffirm and exalt the masculine essence by performing over and over, with ever increasing charisma, the primitive ritual of mortal combat. No wonder, therefore, that Bruce Lee exists for millions of people as a cult figure, who is worshiped—precisely as the ancients worshiped Hercules and Achilles—as a demigod.

It doesn't take any great understanding of Lee to know that he would have been thrilled by his posthumous fame. All his life he struggled to transcend himself and to become more than man. Now he stands exalted in the pop pantheon, unquestionably the most magical figure produced by popular culture since the great days of the sixties. Yes, the Dragon would have gotten off on the idea of immortality. He would have saluted the world with his crazy jungle-bird squawk of triumph.

No comments:

Post a Comment