JFK ASSASINATION SCENE HAD HE LIVED

"God, I hate to go to Texas," Kennedy told a friend, saying he had "a terrible feeling about going."

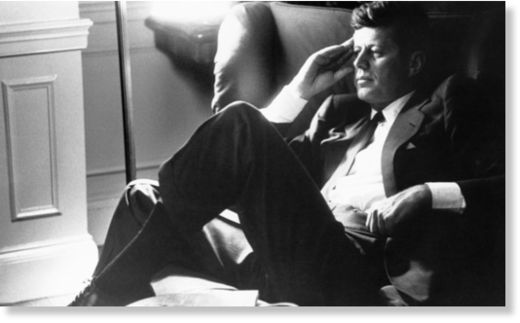

As utterly shocking and traumatic as the assassination of John F. Kennedy was, the one person who might not have been surprised that it happened was JFK himself.

It's worth remembering, as the 50th anniversary of JFK's death approaches, that the young president had a morbid fascination with sudden death - and sometimes speculated that he would die at the hands of an assassin.

"Thank God nobody wanted to kill me today," he said to a friend half a century ago tonight while flying from Florida to Washington. How would it happen? By someone firing at his motorcade from a high window, he thought.

Kennedy also confided in the friend, Dave Powers, that he really didn't want to go to Texas later that week.

"God, I hate to go to Texas," JFK said, adding that he had "a terrible feeling about going."

And on the morning of his murder, Friday, November 22, that terrible feeling was still with him.

"Last night would have been a hell of a night to assassinate a president," he told his wife Jacqueline and Ken O'Donnell, a top aide. William Manchester, in the definitive account of the assassination - Death of a President - picks up the story:

"I mean it," Kennedy said. "There was the rain, and the night, and we were all getting jostled. Suppose a man had a pistol in a briefcase." Then Kennedy "gestured vividly, pointing his rigid index finger at the wall and jerking his thumb twice to show the action of the hammer. "Then he could have dropped the gun and the briefcase" - in pantomime he dropped them and whirled in a tense crouch - "and melted away in the crowd." [Death of a President]Why the fatal fixation? Kennedy - whose favorite poem was "I Have a Rendezvous with Death" by Alan Seeger - knew that for him, for his family, death was always near. He lost his older brother in World War II, when his plane blew up over the English Channel in August 1944. Another plane crash, in May 1948, claimed a sister. He and Jacqueline lost two children: Arabella, their first daughter, delivered stillborn in August 1956, and son Patrick Bouvier Kennedy, who died in August 1963 after just 36 hours. When the infant passed, his father was holding his hand, urging him to hang on; JFK then retreated to a nearby boiler room and broke down in sobs.

Intertwined with these family tragedies were three brushes with death for Kennedy himself. He was given the last rites of his church three times. In 1947, after becoming gravely ill in England. In 1951, he nearly succumbed to a very high fever while visiting Japan. The third time was in 1954 following back surgery to repair his spine: he developed an infection and slipped into a coma for several weeks.

If anything, Kennedy's close calls instilled in him an appreciation for life; both friend and foe described him as a man who understood that time was short and therefore must be lived to the hilt each day. He once predicted he wouldn't live past age 45 (he was off by less than six months) and didn't waste a minute.

Of course, this zeal often manifested itself in unsavory ways. He was, as we all know, a notorious philanderer, bedding everyone from movie stars to wives of close friends to young White House interns.

Then there is this tragic irony: The very understanding that time was limited encouraged him to take risks with his life; that risky behavior may have contributed to his early death. As president, he insisted on riding in open cars whenever possible, and preferred that Secret Service agents be posted, whenever possible, on the follow-up car directly behind his. Unless the weather was bad or there was a known threat, that's the way he liked it. Simply put, John F. Kennedy wanted to be seen, he wanted maximum exposure to voters. A treasure trove of photos from countless trips over the course of his entire presidency belie the conspiracist notion that somehow the security in Dallas in Nov. 22 was different. It wasn't. Indeed, agents that morning at Love Field, where the motorcade was to begin, were wondering whether to put the top (which wasn't bulletproof anyway) on SS100X, Kennedy's 1961 Lincoln Continental. After all, it was drizzling.

A call to the president's top aide, O'Donnell, gave them their answer.

"If the weather is clear and it's not raining, have that bubbletop off," the Secret Service was told.

The skies cleared, and Air Force One, after a 13-minute flight from Fort Worth, landed under brilliant blue skies. It was a good omen, and the president's men always called a day like Nov. 22 "Kennedy weather."